DOH domain name strategy raises security concerns

A new system designed to minimise latency for internet address resolution has raised serious concerns about security and privacy, with potential for third parties to track users and even manipulate what they see online.

The protocol, Domain Name System over Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (DOH) was published in October 2018 to address security concerns over unencrypted data sent between clients and Domain Name System (DNS) servers.

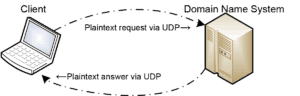

Plain text requests in the transmission chain

Originally, clients typically sent DNS requests via the User Datagram Protocol (UDP) as plain unencrypted text. This permitted end-to-end visibility of the domain name, web link and Internet Protocol address of the client machine throughout the transmission route. Secure communications could then be established with Secure Socket Layer (SSL) or Transport Layer Security (TLS) encryption keys once the destination was identified. However, by this point the nature of the web activity and user identity was already known.

In 2016, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) released an upgraded protocol to resolve this security issue: DNS over TLS, or “DOT”. This method establishes encrypted security between the DNS server and client before submitting the domain name request. However, client uptake of DOT has been limited due to several issues:

- Security negotiations incur latency delays,

- The user must actively choose to implement the system, and some client software is difficult to configure,

- The client system can be identified prior to the encryption negotiation – although this will be resolved by the Encrypted Server Name Indication system in the next TLS update.

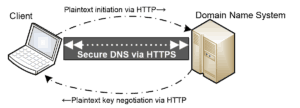

In the meantime, the IETF has released the alternate strategy for accelerated DNS operations: DNS over HTTPS, or “DOH.” DNS resolution details would be incorporated into the header of the transmitted document (web page, media file, etc.) and sent by Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) to the client. This information could include an encrypted listing of DNS information for all links within the current document – and negating the need to send any further DNS requests. The DOH protocol was released in October 2018 and implemented in an Android phone application (Intra) the following month.

Questions raised

The theory sounds plausible. However, the DOH strategy has raised security questions from network experts who are concerned about the impartiality and integrity of data sent within the files.

“Whereas DOT was considered part of the substructure of the environment, HTTP is applications,” said APNIC Chief Scientist Geoff Huston at Melbourne’s APRICOT conference in February 2020.

“All of a sudden, instead of asking the operating system to resolve the name, the browser can do it by itself.

“No one else is involved, and no one else can see it.

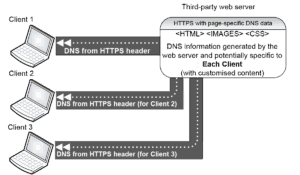

“Once you start doing that individual, tailored subversion, it gets really hard,” he said. “It is encrypted HTTPS, so the DNS resolver knows the user identity, and the user can get a favourite answer that nobody else gets. The resolver can create – for good or bad – tailored results that are invisible to anyone else.”

These DOH requests will be handled by a third party, who may not even by identified by the user. The DNS addresses sent by the server could be manipulated without the user’s knowledge, and without any way to verify the data integrity. A DNS address provided in a web file could be tailored specifically to track the user, or even provide intentionally incorrect data to direct the user to a counterfeit reproduction of their intended destination.

Furthermore, DOH will be able to bypass the web activity rules set by local Internet Service Providers, enterprise policies and legally-enforced internet content law. This could be beneficial or detrimental, depending on the circumstances. Censorship and content control laws could be bypassed and therefore complicate the monitoring of illegal internet user activity or unethical behaviour by internet providers.

These issues were raised in the British House of Lords in May 2019 when Baroness Glenys Thornton detailed her concerns regarding unmoderated internet use and asked for further investigation into the implications of DOH. However, her concerns have not halted the implementation of the protocol. The Google Chrome browser implemented support for DOH throughout the second half of 2019, and Mozilla Firefox followed suit in February 2020.

Geoff Huston believes that the impartiality of the DNS name space needs to be respected as an integral part of the internet and remain independent.

“When you take the DNS resolution away from common infrastructure, for the sake of a few nanoseconds of speed, the results can be finely chopped and fragmented for each user,” he said.

“The common infrastructure DNS is the last piece of cohesion, where everyone asks the same question and gets the same answer.

“This common referential language of the internet is at stake – so it merits the conversation regarding the suitability of DOH.”

References

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=okoA93NUnSU

https://blog.apnic.net/2018/10/12/DOH-dns-over-https-explained/

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc8484

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc7858

https://twitter.com/paulvixie/status/1053765281917661184

https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/t5/networking-blog/windows-will-improve-user-privacy-with-dns-over-https/ba-p/1014229

https://developers.google.com/speed/public-dns/docs/DOH

https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2019-05-14/debates/E84CBBAE-E005-46E0-B7E5-845882DB1ED8/InternetEncryption

https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-ietf-tls-esni/?include_text=1